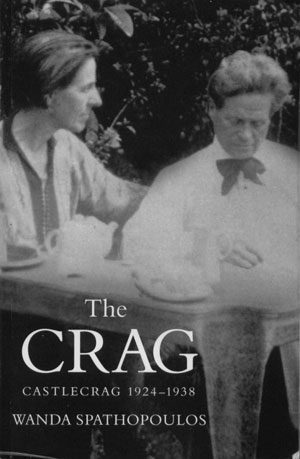

Wanda Spathopoulos, The Crag – Castlecrag 1924-1936. Blackheath, Brandl & Schlesinger, 2007. Paperback, 407 pages, 42 b&w photos. RRP 39.95.

Edgar Herbert, who had spent six years in the United States where he studied physical education, found himself in the same compartment as Walter Burley Griffin on an overnight train journey from Sydney to Melbourne in 1920. Their conversation deeply impressed the educationalist and, following their move from Melbourne to Sydney in late 1922, Edgar and Grace Herbert brought their young family to live at Castlecrag in 1924, initially living in the Griffin-designed King O’Malley house (now the Private Hospital site). In early 1927 the family moved to a weekender shack on Torquay Point where there was ‘no water, no electricity, no sewage, no ice, no bread or milk, and no mail’. There they remained until 1938, but the house that Walter Burley Griffin designed for them would never be completed.

Wanda Spathopoulos’ book, which comprises memoirs of her childhood in Castlecrag supplemented by subsequent research into the period, provides a valuable record of the Castlecrag community in its founding years. Every member of each household during this 14 year period is covered it seems. Walter and Marion Griffin play dominant roles of course, but the real heroes to emerge from the tale are Edgar and Grace Herbert. Like the Griffins, they were driven by a deep commitment to humanity and a desire to help others. Like the Griffins, economic times did not smile on Edgar Herbert and he and his family lived in poverty for much of their time in Castlecrag; but his spirit and strong moral values never wavered. Wanda has done us all a service in documenting much of the Herbert family’s life in this book, from Edgar’s chance meeting with Griffin in 1920 through to the frustrations of his latter years when the Sydney YMCA thwarted his plans for advancement in order to keep the local physical education college going.

Perhaps the most important and fascinating feature of this book is the insight it provides into the magical environment and culture in which the children of the early Castlecrag grew up. I suspect it was not Wanda’s main intention, but she has conveyed much of the feeling of freedom, exploration and interaction with nature that the Castlecrag peninsula offered its children—it was an idyllic childhood that people who grew up in Castlecrag into the 1950s and early 1960s continue to look back on with nostalgia, but sadly appears to have been lost in the world of mass consumerism, electronic entertainment and organised events that now dominate family life.

For the Herbert girls in particular, Marion Mahony Griffin became a powerful influence on their childhood. In her grand work, Magic of America, Marion states: ‘All my life the time I have spent with children, always borrowed since I had none of my own, has been spent in making them “naughty”. To me it was an obvious perversion of nature to try to instil moral notions into little children and a very apparent imposition on the part of grown-ups to make life easier for themselves at no matter what cost of loss of character to the young.’ Then of Castlecrag, she states: ‘In this bush a child could roam at will. Children should no more be brought up in houses than colts and calves.’ (Part III, p. 124)

The Herbert girls, Irven and Wanda, spent long hours with Marion and followed her rules on the freedoms they were allowed, particularly never disturbing the work of the architectural staff. Wanda, the younger, initially found Marion distant and overbearing, but these memoirs are a testament to the influence Marion had over her. To Wanda, ‘Marion was dynamic; Marion was magic’. [From speech at book launch] As soon as she was able, Wanda went overseas in search of the Greek gods that Marion had introduced her to, married a Greek and lived there for much of her adult life.

Of Walter Burley Griffin we learn rather less. Most of the characters in this story have a deep admiration for Walter’s architecture and the philosophy that lay behind it, but the man himself remains a distant and shadowy figure.

This book makes an important contribution to our understanding of the history and character of the Castlecrag of the 1920s and 1930s and is recommended reading for all local residents. It should, however, be seen as a memoir, albeit supported by a considerable amount of follow-up research, and many of the facts and interpretations will be open to contrary views. The book would have benefited by a more rigorous edit, for there is much that is peripheral to the central story in its 407 pages. And while several of the intertwined chapters on the author’s life in Greece provide a useful platform from which to appreciate the Griffins’ design concepts for Castlecrag, this reviewer failed to see the purpose of the majority and found them distracting.

Bob McKillop